The cultural evidences of Tai’s Naga believe along the Mekong River Basin.

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.69598/decorativeartsjournal.3.57%20-%2077Keywords:

cultural evidence, Naga believe, Tai ethnic along Mekong River BasinAbstract

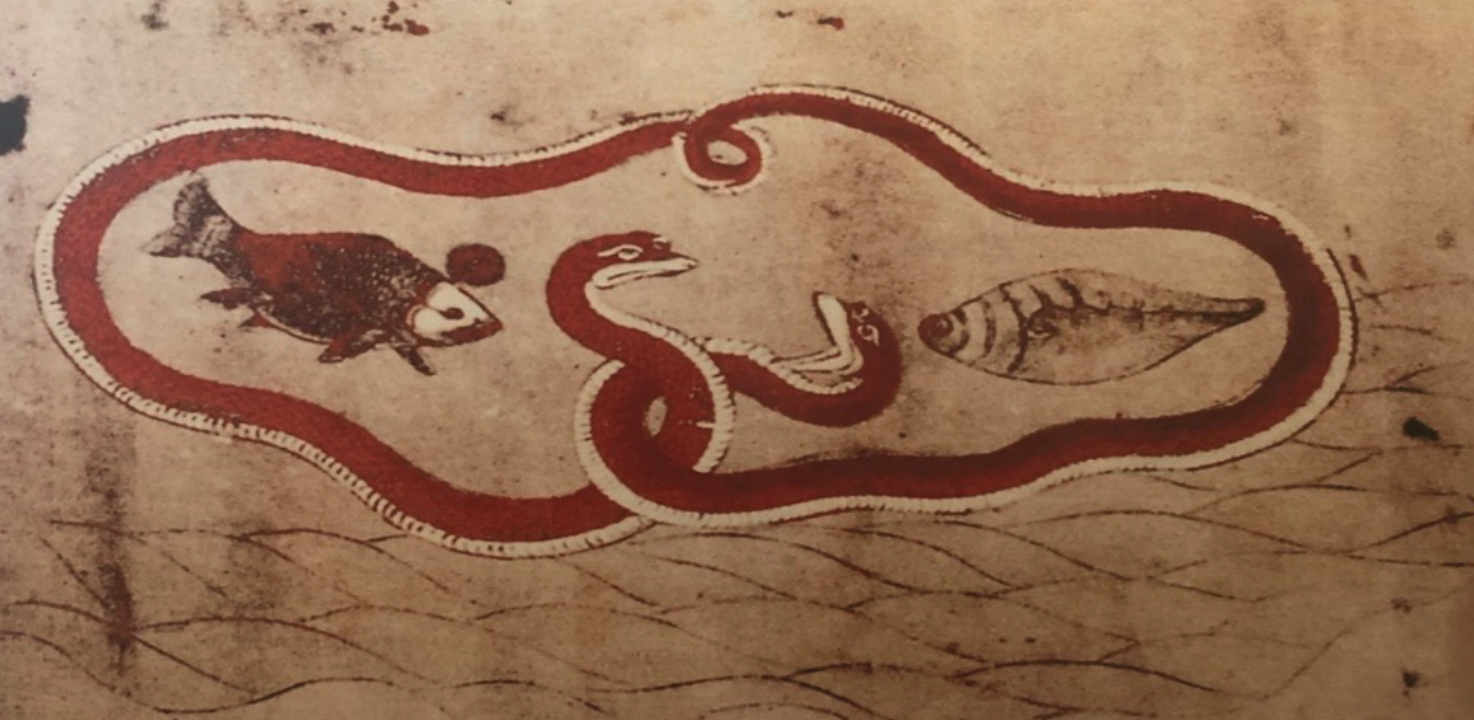

The aim of this article was to review literature, art, and antiquities based on historical and anthropological information regarding the relationship between the north and north east of Thailand and the Tai - Kadai speaking peoples of Erhai Lake in China's Yunnan Province. Study by compiled the discovery of ancient artefacts’ report, stories, legends, literatures and art forms, including assumptions that many scholars have made over a long period of decades. The timeline was summarized from cultural evidence through beliefs about Naga. The result was to collect information and update it for researchers, academics, and interested person to convenient their research or reference. Although the legend of Naga in Thai – Laos, the origin of the Naga in the Mekong River Basin and its tributaries comes from Nong Sae. Whereas the archaeological evidence indicates that the aspect of Naga did not originate in the Nong Sae or Erhai Lake in Yunnan Province. In fact, it is the result of exchange and assimilation between the Indian civilization and the southern Chinese ethnic tribes. Considering the seriation of archaeological evidence, it can be seen that the belief in the Naga entered Southeast Asia through Buddhist merchants and monks from the Krishna-Godavari river basin around the 1th – 3th centuries. The early evidences appearing in the port communities which accessible from merchant ships on both the Bay of Bengal and the Gulf of Thailand. While the Indian-style Naga appeared in Khmer culture around the 6th century. Therefore, the Naga aspects from the Nan Zhao scrolls was dating estimated in the 9th century. Another assumption was about the conflict of 2 Nagas appeared in the Thai -Lao legend and in the Nan Zhao scroll. The Erhai picture in Nan Zhao scroll illustrated an image of two Nagas’ attendants, a gold fish carring money and a jade conch. The key success factor of the coinage system was necessary to set standards from the governor. Thus, the goldfish carring coin is not only a form of an animal. Rather, it reflects the acceptance of the state economic system based on power from the Han rulers. Eventually, the Bai culture group around Erhai Lake was assimilated into the Han culture while the Tai-Lao group spread out along the Mekong Basin and its tributaries. Still favoring the nature of an independent economy that was not bound by standards from the central government as colonial countries. Basic habits that favor a simple, economic system along with the art of not being governed, it is an important geopolitical core that makes the Tai ethnic group separate the center from those in southern China. Therefore, the Naga culture still appears in the folk culture of the Mekong Basin and its tributaries today. Meanwhile, the Yunnan area has been assimilated by the dragon gods of the Han culture, leaving only sparse evidence today.

References

กรมศิลปากร. (2537). อุรังคธาตุ ตำนานพระธาตุพนม. เรือนแก้ว.

ชลธิรา สัตยาวัฒนา. (2561). ด้ำ แถน กำเนิดรัฐไท สาวรกรากต้นตอ คนไท ชุมชนไท-ลาว และความเป็นไท/ไต/ไทย/สยาม. ชนนิยม.

ปฐม หงษ์สุวรรณ. (2554). แม่น้ำโขง: ตำนานปรัมปราและความสัมพันธ์กับชนชาติไท. [รายงานวิจัยฉบับสมบูรณ์]. คณะมนุษยศาสตร์และสังคมศาสตร์ มหาวิทยาลัยมหาสารคาม.

บุญศรี ประภาศิริ. (2478). วิเคราะห์เรื่องเมืองไทเดิม. [พิมพ์ในงานปลงศพ นายหลี เสฐียรโกเศศ]. ท่าพระจันทร์.

ผาสุข อินทราวุธ. (2542). ทวารวดี การศึกษาเชิงวิเคราะห์จากหลักฐานทางโบราณคดี. อักษรสมัย.

ผาสุข อินทราวุธ. (2543). พุทธปฎิมาฝ่ายมหายาน. อักษรสมัย.

ศิราพร ณ ถลาง. (2539). รายงานวิจัยเรื่องตำนานสร้างโลกของคนไท. มหาวิทยาลัยสุโขทัยธรรมาธิราช.

ศิริศักดิ์ อภิศักดิ์มนตรี (2563). ตำนานอุรังคธาตุ: นาคอยู่ในสุวรรณภูมิ ไม่มีนาคที่พระธาตุพนม. วารสารปณิธาน, 16(2) (กรกฎาคม-ธันวาคม 2563), 149.

Colin Mackerras. (1988). Aspects of Bai Culture: Change and Continuity in a Yunnan Nationality. Modern China, 14(1),51-84.

James C. Scott. (2009). The Art of Not Being Governed An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. Yale University Press.

Robert Knox. (1992). Amaravati Buddhist Sculpture from the Great Stupa. British Museum Press.

Wang,S.W. (1979). Yunnan Valley Lost Book Banknotes. Yunna People’s Publishing House.

Wen, Y.C. (2001). An Examination and Explanation of the Literal Volume of The Illustrated History of Nan Zhao . Studies in World Religions, 1(2).

Yang Yuexiong. (2020). The Historical Evolution of the Water God of the Bai People and Its Significance. Journal of Ethnology, 11(2),110 – 117. DOI : 10.3969/j.issn. 1674 – 9391. 2020. 02. 015.

Zhang Shengwen (n.d.). 宋時大理國描工張勝溫畫梵像卷張勝溫.

from https://digitalarchive.npm.gov.tw/Painting/Content?pid=14458&Dept=P

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

Categories

License

Copyright (c) 2024 DEC Journal

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Published by Academic Affairs Division, Faculty of Decorative Arts, Silpakorn University. The copyright of the article belongs to the article owner. Published articles represent the views of the authors. The editorial board does not necessarily agree with and is not responsible for the content of such articles.